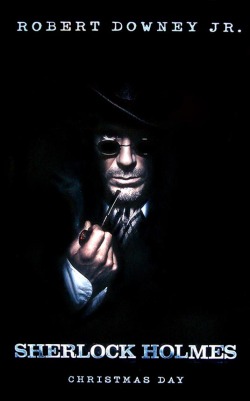

Review: Sherlock Holmes (2009)

It’s official: Guy Ritchie can still make a good movie.

It’s official: Guy Ritchie can still make a good movie.

Sherlock Holmes isn’t as memorable as Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels or Snatch, but it’s a fun time in the theater and that’s all I was really looking for. From the very beginning, it’s clear that Ritchie knows how to handle a big-budget blockbuster: the costumes are lavish, the architecture is ornate, and the set design screams “19th Century London.” The script and art direction perfectly capture the Age of Enlightenment, from the wheels and cogs of the Industrial Revolution to the extreme emphasis on rationalism and the mistrust of religion.

But this isn’t your grandfather’s Sherlock Holmes. This is a Holmes who seems to enjoy beating people up as much as proving he’s smarter than they are. He frequents bare-knuckle boxing arenas (complete with Ritchie’s trademark slow-mo fistfights), takes on henchmen twice his size, and doesn’t think twice about leaping out of tall buildings. This is a Holmes with balls as big as his brains, the kind of detective a 21st-century audience can get behind. Ritchie directs the action set-pieces with a frenetic energy that feels exciting without being disorienting. While there’s quick-cutting galore, there’s no shaky-cam to distract from the geography of the scene, and as a result Sherlock Holmes is at the very least a fun romp through back-alley London.

The performances are all solid. Robert Downey, Jr. brings just the right amount of sarcastic hubris and emotional confusion to a character that would otherwise be unlikeable. Jude Law makes Watson a worthwhile character in his own right, rather than simply a frustrated sidekick to Holmes’ adventures. He has a will of his own, and his frequent tiffs with his former boss provide some of the film’s most charming moments. Rachel McAdams plays the part of manipulated seductress well, and Mark Strong adds a sinister presence to the evil snaggle-toothed Blackwood that keeps the character from feeling too familiar.

The main problem with Sherlock Holmes is that it treats its audience like its title character treats… well, everybody. Holmes is such an intellectual ubermensch that it’s barely possible for anyone else to understand his conclusions, let alone how he got to them. His hubris rivals that of all the great minds throughout history – he’s a genius, and he knows it. The problem is that nobody likes an arrogant egomaniac, and the film suffers from the same tone of superiority. It presents the enormously detailed and complex solutions to various mysteries with such gusto that it’s hard not to feel that, like Sherlock himself, it’s talking down to its audience. And I don’t like being treated like a child.

The main problem with Sherlock Holmes is that it treats its audience like its title character treats… well, everybody. Holmes is such an intellectual ubermensch that it’s barely possible for anyone else to understand his conclusions, let alone how he got to them. His hubris rivals that of all the great minds throughout history – he’s a genius, and he knows it. The problem is that nobody likes an arrogant egomaniac, and the film suffers from the same tone of superiority. It presents the enormously detailed and complex solutions to various mysteries with such gusto that it’s hard not to feel that, like Sherlock himself, it’s talking down to its audience. And I don’t like being treated like a child.

The best mysteries are the ones that audience members feel like they can solve themselves, particularly on repeat viewings. Why do we re-watch movies like The Sixth Sense, or The Usual Suspects, or Memento? Not only are they fine movies in their own right, but we like catching the details we missed the first time around. We like to notice new pieces of the puzzle and how they all fit together within the larger frame of the narrative. In essence: we like mysteries that aren’t easy enough to figure out on the first viewing, but have solutions that are apparent enough that on repeated viewings we get to feel smarter than the protagonist.

It’s with the latter concept that Sherlock Holmes fails. It doesn’t matter how many times audiences watch this film, they’re unlikely to come away feeling much smarter by the end. At the end of the day, I still don’t know enough about chemistry, pagan mythology and the properties of certain elements to understand what exactly Holmes is deducing, let alone how he’s deducing it. He will always be the smartest man in the room, even when the audience knows what’s coming. I don’t mind following a protagonist who’s undoubtedly more observant and intelligent than I am. But if I’m constantly confronted with problems that can only be solved with an encyclopedic knowledge base that very few people have, after a while I’ll start feeling dumb, rather than entertained. This is especially true when Holmes doesn’t reveal what he knows as soon as knows it, but chooses instead to wait until the end of the film to unveil the answer to every unanswered question. We’re not even allowed a hint of insight into how his massive cranium works, and the result is rather alienating. There is Sherlock Holmes, and then there is Everybody Else, with no room for overlap.

It’s with the latter concept that Sherlock Holmes fails. It doesn’t matter how many times audiences watch this film, they’re unlikely to come away feeling much smarter by the end. At the end of the day, I still don’t know enough about chemistry, pagan mythology and the properties of certain elements to understand what exactly Holmes is deducing, let alone how he’s deducing it. He will always be the smartest man in the room, even when the audience knows what’s coming. I don’t mind following a protagonist who’s undoubtedly more observant and intelligent than I am. But if I’m constantly confronted with problems that can only be solved with an encyclopedic knowledge base that very few people have, after a while I’ll start feeling dumb, rather than entertained. This is especially true when Holmes doesn’t reveal what he knows as soon as knows it, but chooses instead to wait until the end of the film to unveil the answer to every unanswered question. We’re not even allowed a hint of insight into how his massive cranium works, and the result is rather alienating. There is Sherlock Holmes, and then there is Everybody Else, with no room for overlap.

Overall, Sherlock Holmes makes for some enjoyable escapist entertainment, and I’ll definitely be seeing the inevitable sequel. I’m just hoping that I won’t feel as dumb after that one as I did after this one. I remember re-watching The Sixth Sense for the first time and thinking to myself, “Of course! It’s so obvious! How could I not have figured it out before?” I have a feeling if I re-watch Sherlock Holmes I’ll still just end up thinking, “Ammonium what-now? Whatever you say, good chap!”