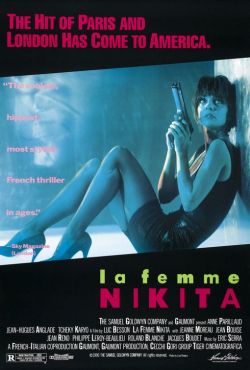

Review: La Femme Nikita (1990)

Note: This review contains spoilers.

La Femme Nikita received fairly poor reviews upon its release twenty years ago. Despite the negative reception, it has had tremendous impact in popular culture, spawning a remake and multiple television series. It helped establish director Luc Besson as one a new and innovative action filmmaker. Does it hold up? Overall, yes. Though it’s brought down by a weak third act, La Femme Nikita is a refreshing take on the now-clichéd “government agency hires thug to be highly-effective super agent for some reason” plotline, combining well-executed action scenes with compelling performances and a fantastic synth score.

The plot follows Nikita (Anne Paurillard), a drug addict who kills a policeman when a pharmacy break-in goes wrong. She’s sentenced to life in prison, but a secret government organization intervenes and drugs her. When she comes to, she no longer exists. Her death has been faked and her life is not her own. Their goal is to mold her into an elite assassin. If she resists, she’ll be killed.

Anne Paurillard carries this film on her shoulders and elevates it above a typical action thriller. Her performance is so varied in its extreme range of Nikita’s personality quirks that at times I couldn’t believe I was watching the same woman. At the beginning of the film, Nikita is a drugged-up, aggressive, borderline psychotic teenager with nothing but a quick wit and temper to indicate she might, somehow, be able to eventually become a productive member of society. She’s disheveled, wide-eyed and so mentally unhinged that I was convinced, despite knowing the basic premise of the film, that she was doomed to die having failed to properly adapt to any sort of physical, mental or social training whatsoever. She was simply too far gone.

Besson wisely chooses to forego the usual training montage route, instead showing us a single scene in which Nikita, having learned that she has two weeks to start showing progress or else, sits in front of a mirror and studies herself. Paurillard’s expression contains just the right amount of self-loathing with a glimmer of resolve and hope. She picks up some lipstick. Cut to three years later, she’s Wonder Woman. She’s refined, elegant, beautiful, confident. Whatever part of her mind had been trapped in a drug-induced haze has been freed from its insecurities and is now working at top capacity. Drug rehab centers take note: apparently makeup is the cure to addiction and mental illness. Just make them look pretty and they’ll be fine. In any other film, this extreme change would feel out of place and unrealistic. Paurillard makes it work through a nuanced performance that manages to communicate subtle revelations about Nikita’s complex psychology even during extreme outbursts and manic behavior.

Besson wisely chooses to forego the usual training montage route, instead showing us a single scene in which Nikita, having learned that she has two weeks to start showing progress or else, sits in front of a mirror and studies herself. Paurillard’s expression contains just the right amount of self-loathing with a glimmer of resolve and hope. She picks up some lipstick. Cut to three years later, she’s Wonder Woman. She’s refined, elegant, beautiful, confident. Whatever part of her mind had been trapped in a drug-induced haze has been freed from its insecurities and is now working at top capacity. Drug rehab centers take note: apparently makeup is the cure to addiction and mental illness. Just make them look pretty and they’ll be fine. In any other film, this extreme change would feel out of place and unrealistic. Paurillard makes it work through a nuanced performance that manages to communicate subtle revelations about Nikita’s complex psychology even during extreme outbursts and manic behavior.

The film chugs along at a pace that allows for the perfect balance between action and character development. In the second act we’re introduced to another familiar plotline: the ol’ “agent-struggling-to-lead-a-normal-life” routine. She falls in love with Marco (Jean-Hugues Anglade), a grocery store clerk who couldn’t possibly pose any sort of threat. Somehow, it works. Their relationship is so innocent and natural – he’s a romantic and she’s desperate for a normal life – that I found myself wanting it all to work out. Even scenes in which she’s forced to hide her true identity feel believable, and that’s not an easy accomplishment.

Unfortunately, the final third of the film is a jumble of plot lines and character threads. The always-impressive Jean Reno enters the mix as a cleaner when one of Nikita’s missions is botched, but he’s never given room to breathe. The final sequence of events occurs so quickly that it’s hard to keep track of the details – who’s trying to do what, who’s getting in the way, and what the possible solutions could be. It’s so haphazard that in one fell swoop I was taken nearly entirely out of the film. It’s a disappointing finish to what was shaping up to be a truly impressive genre picture.

Unfortunately, the final third of the film is a jumble of plot lines and character threads. The always-impressive Jean Reno enters the mix as a cleaner when one of Nikita’s missions is botched, but he’s never given room to breathe. The final sequence of events occurs so quickly that it’s hard to keep track of the details – who’s trying to do what, who’s getting in the way, and what the possible solutions could be. It’s so haphazard that in one fell swoop I was taken nearly entirely out of the film. It’s a disappointing finish to what was shaping up to be a truly impressive genre picture.

Though La Femme Nikita is often held up as an example of a noteworthy film that helped pioneer the idea of a woman as an action hero, its gender politics aren’t nearly as progressive upon close inspection. Nikita’s identity as a woman is socialized onto her by a mysterious government agency, her primary contact with which is through the simply-named handler “Bob” (Tcheky Karyo). Though she’s also taught cosmetics and the art of seduction by a woman named Amande, the advice she gets doesn’t move beyond the realm of the sexual. “There are two things that are infinite: femininity and the means to take advantage of it,” Amande explains.

The men in Nikita’s life control her mission, her training, her identity (through the use of code names) and her location. Whatever agency she has is limited to being under their overarching guidelines. The only thing she has to herself is her body. After a high-tension shootout during a final training exercise – one of the highlight scenes of the film – her Freudian father-daughter relationship with Bob finally boils and she kisses him briefly on the lips. “That’s the last kiss you’ll ever get from me,” she states. He stands stunned outside her room, leaning against the wall, and the camera stays frozen on him for several seconds. He is devastated. That’s the extent of Nikita’s power. She can use her sexuality to manipulate the hearts of men. Unfortunately, they can control pretty much everything else about her.

The men in Nikita’s life control her mission, her training, her identity (through the use of code names) and her location. Whatever agency she has is limited to being under their overarching guidelines. The only thing she has to herself is her body. After a high-tension shootout during a final training exercise – one of the highlight scenes of the film – her Freudian father-daughter relationship with Bob finally boils and she kisses him briefly on the lips. “That’s the last kiss you’ll ever get from me,” she states. He stands stunned outside her room, leaning against the wall, and the camera stays frozen on him for several seconds. He is devastated. That’s the extent of Nikita’s power. She can use her sexuality to manipulate the hearts of men. Unfortunately, they can control pretty much everything else about her.

The conflict between woman as object and woman as free agent is one that frequently pops up in mainstream cinema (though usually through a depiction of the former), and Besson’s treatment of the matter is muddled. Though Nikita does demonstrate some agency of her own, she’s still presented as the object of male desire. During one mission she’s required to don a maid outfit and change in front of roomful of thugs. On another job, she assembles a sniper rifle and assassinates her target while in a bra and panties. There’s a fine line between female sensuality as tool of empowerment and a tool of oppression, and unfortunately Nikita frequently falls back into stereotypes that promote the latter.

It’s easy to see why La Femme Nikita spawned an American remake and two television shows. The plot is simple, yet there’s tremendous potential for entertaining action and genuine thematic depth. Unfortunately, it’s only two-thirds of a great film. But boy, are those two thirds solid.