The Year's Best: The Broadway Melody (1929)

The Year's Best is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at films declared the “Best Picture” of a particular year by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. These posts are not intended as discussions of whether or not these films “deserved” to win. Rather, they are simply my musings and thoughts on what are supposedly the cream of the crop of American cinema.

The Year's Best is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at films declared the “Best Picture” of a particular year by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. These posts are not intended as discussions of whether or not these films “deserved” to win. Rather, they are simply my musings and thoughts on what are supposedly the cream of the crop of American cinema.

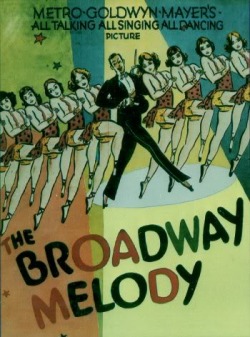

Title: The Broadway Melody

Director: Harry Beaumont

Starring: Bessie Love, Anita Page, Charles King

Oh, the late 1920s. It was a time of change for Hollywood. Film studios were still transitioning into the sound era – the technology was not yet perfected, and most theaters were still not equipped for audio, meaning that most films had to be shot and edited for both “talkie” and silent versions. It was in this context that MGM began producing films in what would come to be its most popular and well-known genre: the musical. The Broadway Melody was released in 1929 and was a critical and commercial success, grossing a record $4 million at the box-office and going on to become the second winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Unfortunately, though it’s considered the “grand-daddy of musicals,” The Broadway Melody is a pretty mediocre film by today’s standards. It’s clear that Hollywood was struggling to adapt to the new sound technology. Microphone range and placement limited camera placement. Actresses who were stars in the silent era were frequently unable to adapt to the new style of acting, and those who were often faded from the limelight after the public didn’t like their voices. The Broadway Melody carries the scars of an industry confronted with rapidly-changing technology: stiff acting, a formulaic script, and bland cinematography.

The plot follows The Mahoney Sisters, a two-sister vaudeville act that goes to New York to try and make their fortune on Broadway. Harriet Mahoney (Bessie Love) has a boyfriend, Eddie (Charles King), who’s a stage hand for some major theater players. But things get complicated when Eddie starts to fall for her sister, Queenie (Anita Page). It’s a typical love triangle, compounded only by the fact that the two women in question are related. Even at this early stage in the history of film, it was the type of story that had been done before, so if you’re looking for originality you won’t find it here.

The musical numbers in The Broadway Melody, though they were the film’s major selling point, are by today’s standards its worst feature. The sound mixing is pretty terrible; I frequently found myself struggling to hear the lyrics over the instruments, and even when they could clearly be heard it was difficult to make out the exact words. Only one number makes use of any elaborate sets and props, and even these are barely impressive and hampered by bland cinematography. The only noteworthy tracks were “The Wedding of the Painted Doll,” which in early prints was shot in red-green Technicolor, and “You Were Meant For Me,” which would become so popular it would later pop up in other musicals, like Singin’ In the Rain. While The Broadway Musical was immensely popular and would spawn three sequels, it’s clear that at this point in time Hollywood was struggling to find its footing in the sound era. Perhaps this was obvious even at the time – many critics view the competing films as equally unimpressive - and that’s why it went down in history as the first of only 3 films to win Best Picture without receiving any other Academy Awards (though Bessie Love was nominated for Best Actress).

The musical numbers in The Broadway Melody, though they were the film’s major selling point, are by today’s standards its worst feature. The sound mixing is pretty terrible; I frequently found myself struggling to hear the lyrics over the instruments, and even when they could clearly be heard it was difficult to make out the exact words. Only one number makes use of any elaborate sets and props, and even these are barely impressive and hampered by bland cinematography. The only noteworthy tracks were “The Wedding of the Painted Doll,” which in early prints was shot in red-green Technicolor, and “You Were Meant For Me,” which would become so popular it would later pop up in other musicals, like Singin’ In the Rain. While The Broadway Musical was immensely popular and would spawn three sequels, it’s clear that at this point in time Hollywood was struggling to find its footing in the sound era. Perhaps this was obvious even at the time – many critics view the competing films as equally unimpressive - and that’s why it went down in history as the first of only 3 films to win Best Picture without receiving any other Academy Awards (though Bessie Love was nominated for Best Actress).

The only thing about The Broadway Melody that struck me as slightly odd and unique was the relationship between Harriet and Queenie. At first, I didn’t pick up on the fact that they were sisters, and was surprised at the quasi-sexual nature of their relationship. Upon arriving in New York, Harriet kisses Queenie on the lips, and I found myself thinking, “Lesbians? In a film from 1929?!” Once I realized they were sisters, things started to make more sense, but there are still a few moments that make me question whether or not the writers intentionally wanted there to be undertones of incest. Their very names carry hints of what in 1929 would have been considered sexual deviancy: Harriet frequently goes by the male moniker “Hank” and “Queenie” brings with it associations with homosexual males. Perhaps this was purposeful on behalf of the filmmakers, or maybe I’m just a pervert.

The only thing about The Broadway Melody that struck me as slightly odd and unique was the relationship between Harriet and Queenie. At first, I didn’t pick up on the fact that they were sisters, and was surprised at the quasi-sexual nature of their relationship. Upon arriving in New York, Harriet kisses Queenie on the lips, and I found myself thinking, “Lesbians? In a film from 1929?!” Once I realized they were sisters, things started to make more sense, but there are still a few moments that make me question whether or not the writers intentionally wanted there to be undertones of incest. Their very names carry hints of what in 1929 would have been considered sexual deviancy: Harriet frequently goes by the male moniker “Hank” and “Queenie” brings with it associations with homosexual males. Perhaps this was purposeful on behalf of the filmmakers, or maybe I’m just a pervert.

Overall, The Broadway Melody is worth seeing if you’re interested in early sound cinema or the musical genre. But if you’re looking for an innovative story and flashy song-and-dance numbers, you should probably look somewhere else. It’s hard to blame director Harry Beaumont, a veteran of silent films, for the movie’s mediocrity. Like the industry in general, he was struggling to cope with new game-changing technology. Though it isn’t a fantastic film, The Broadway Melody would go on to provide a jumping-off point for the musical, which would go on to become one of the most popular and respected genres in the medium. In that respect, it truly is noteworthy.