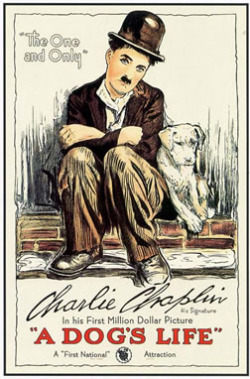

The Chaplin Chapters: A Dog's Life (1918)

A Dog's Life is one of six Chaplin short films I saw at the recent Janus Films retrospective at the Carolina Theatre in Durham. It's noteworthy for being the first movie that Chaplin directed for First National Films - their contracts with him and Mary Pickford were the first million dollar contracts in film history. Not only that, but it also pairs Chaplin up with a canine co-star, a "thorough-bred mongrel" named Scraps according to the title cards. All in all, it's one of the more enjoyable shorts I saw, and contains several of the dominant themes that characterized Chaplin's work.

A Dog's Life is one of six Chaplin short films I saw at the recent Janus Films retrospective at the Carolina Theatre in Durham. It's noteworthy for being the first movie that Chaplin directed for First National Films - their contracts with him and Mary Pickford were the first million dollar contracts in film history. Not only that, but it also pairs Chaplin up with a canine co-star, a "thorough-bred mongrel" named Scraps according to the title cards. All in all, it's one of the more enjoyable shorts I saw, and contains several of the dominant themes that characterized Chaplin's work.

The film opens with Chaplin as his famous Tramp character, sleeping in the dirt behind a fenced-in area. He awakens to find a food salesman on the other side of the fence with a bucket full of tasty meat. But just as he's reaching through the fence to steal some breakfast, he's spotted by a police officer. This leads to a humorous back-and-forth chase scene that touched on a common theme in Chaplin's work: the police not as protectors of society but as obstacles to lower-class survival. It's no wonder that his films were so popular among immigrants and the working class. Not only could his silent comedy transcend the language barrier, but his Tramp character was someone many could relate to. The United States was still in the middle of a wartime economy, not having yet reached the Roaring Twenties, and Tramp in many ways provided an outlet for lower-class frustration. In A Dog's Life, Tramp doesn't even remotely pretend to be a gentleman, as he does in other Chaplin films. He's mangy, dirty and ragged. A swift kick in the pants of a police officer not only allowed audiences to laugh at authority figures, but it captured the class tension many people dealt with every day.

For example, another scene finds Tramp at an employment agency so he can get a temporary job at a brewery. He waits on the bench for the clerk to call him up, but a line of other employed men soon pushes him off. He's forced to go to the back of the line, and then when it's finally his turn, he can never make it in time. He runs back-and-forth between stations, each time always one step behind someone else. After a few minutes, all the jobs are taken, and he's left with nothing. Who among us hasn't felt like a job we were suited for was taken from us by someone else, even though we were there first? Especially in a recession. Chaplin's Tramp character isn't just a vagrant here, he's a symbol of the American working class.

For example, another scene finds Tramp at an employment agency so he can get a temporary job at a brewery. He waits on the bench for the clerk to call him up, but a line of other employed men soon pushes him off. He's forced to go to the back of the line, and then when it's finally his turn, he can never make it in time. He runs back-and-forth between stations, each time always one step behind someone else. After a few minutes, all the jobs are taken, and he's left with nothing. Who among us hasn't felt like a job we were suited for was taken from us by someone else, even though we were there first? Especially in a recession. Chaplin's Tramp character isn't just a vagrant here, he's a symbol of the American working class.

All this eventually leads to an encounter with Scraps, the aforementioned mutt. In a scene mirroring Tramp's unsuccessful attempts to find a job, Scraps finds a morsel of food in the road. Though he gets there first, it isn't long until he's attacked by other stray and starving dogs who attempt to steal it away from him. Chaplin rescues the animal before it's too late, and the two are soon inseparable. They are spiritual soul mates, each one rejected by society and fighting for survival.

In one of the film's most memorable scenes, Tramp attempts to take Scraps into a bar with him. Unfortunately, there's a no pet policy. Rather than tying up Scraps outside, Tramps does the thing that seems most obvious to him: he shoves Scraps down his trousers, with nothing but a tail poking out as any indication of his trickery.

While in the bar, he meets a beautiful singer, who moves all of the customers to tears by singing an old song. She's played by Chaplin's real-life ex-girlfriend, Edna Purviance - though their relationship was over, she'd continue to appear in his films for most of his career. In a perfect example of Chaplin's concise, rhythmic writing, the manager encourages her to flirt with the male patrons: "If you smile and wink, they'll buy a drink." When Tramp innocently approaches her, she winks and motions with her head to such an extreme that he thinks she must have something in her eye. Cue the title card with her response: "I'm flirting." It's a joke so blunt and deadpan that it reminded me of something out of a Joss Whedon script. Say what you will about Chaplin, it can't be denied the man perfectly understood several different types of comic devices.

All of this leads into the film's second half, which largely revolves around some stolen money. A couple of thugs pick-pocket a wealthy man and bury the envelope of cash in the same fence-enclosed dirt area that Tramp sleeps at night. Scraps digs it up, but eventually it winds up back in the hands of the criminals who originally took it. In another of the film's highlight scenes, Tramp sneaks into the back room of the bar where they're getting drunk off their newfound wealth and through a fantastic sight gag manages to knock them both unconscious and get the money back. This leads to a climactic chase scene involving the crooks and the police, but Scraps manages to save the day and bring the money to Tramp. The final scene is of him and the bar singer at a beautifully adorned country home, as they live happily ever after with a cradle full of newborn puppies. "When dreams come true," reads the title card that introduces the scene, alluding to another motif Chaplin was fond of: dreams. The conflict between reality and fantasy is one that his early work would frequently reference - this is one of the rare occasions where it's implied the happy life he longs for and real life are one and the same.

All of this leads into the film's second half, which largely revolves around some stolen money. A couple of thugs pick-pocket a wealthy man and bury the envelope of cash in the same fence-enclosed dirt area that Tramp sleeps at night. Scraps digs it up, but eventually it winds up back in the hands of the criminals who originally took it. In another of the film's highlight scenes, Tramp sneaks into the back room of the bar where they're getting drunk off their newfound wealth and through a fantastic sight gag manages to knock them both unconscious and get the money back. This leads to a climactic chase scene involving the crooks and the police, but Scraps manages to save the day and bring the money to Tramp. The final scene is of him and the bar singer at a beautifully adorned country home, as they live happily ever after with a cradle full of newborn puppies. "When dreams come true," reads the title card that introduces the scene, alluding to another motif Chaplin was fond of: dreams. The conflict between reality and fantasy is one that his early work would frequently reference - this is one of the rare occasions where it's implied the happy life he longs for and real life are one and the same.

Overall, A Dog's Life is an enjoyable short, keeping a brisk pace throughout its 33-minute runtime and never wearing out its welcome. Chaplin's direction, writing and score are all top-notch. It's also one of the few Tramp films I've seen that has an outrageously happy ending in which he actually gets the girl and appears to achieve upward class mobility. And yet, it's worth pointing out that even in the final scene he isn't an uptight, wealthy member of the bourgeoisie; at best, he's a farmer living an idyllic middle-class existence with the love of his life and their furry "children." He'll never become an oppressive elitist, but he will find happiness and prosperity. It's that kind of personal triumph that made Chaplin relatable to audiences around the globe, and continues to make his films resonate today.