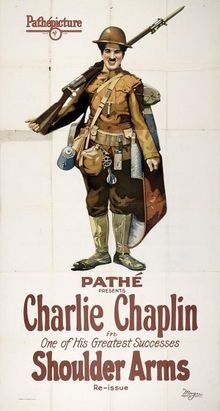

The Chaplin Chapters: Shoulder Arms (1918)

One of the other short films I saw at the Carolina Theatre's recent Charlie Chaplin retrospective was Shoulder Arms, his second film for First National Pictures following A Dog's Life. To say they're completely different films with little in common would be putting it mildly. Whereas the latter is an optimistic and light-hearted comedy, Shoulder Arms is a much more cynical film about a very heavy issue: war. Released during the later part of World War One, it would be his most popular film yet, both commercially and critically.

One of the other short films I saw at the Carolina Theatre's recent Charlie Chaplin retrospective was Shoulder Arms, his second film for First National Pictures following A Dog's Life. To say they're completely different films with little in common would be putting it mildly. Whereas the latter is an optimistic and light-hearted comedy, Shoulder Arms is a much more cynical film about a very heavy issue: war. Released during the later part of World War One, it would be his most popular film yet, both commercially and critically.

The film opens with Chaplin playing an army recruit in training camp. He seems completely unsuited for the military, unable to handle a gun properly and even having trouble marching. After a hard day of training, he returns to his tent and collapses on the bed, exhausted.

The next scene finds him in the trenches in the heat of battle. The comedy in this portion of the film revolves mainly around the harsh conditions faced by American soldiers - using jokes to shed light on the horrors of war. For example, in one slighty melancholic scene, he receives no letters from home, and must resort to secretly reading another soldier's correspondence behind his back. Another gag involves the one package he does receive from home: a container of limburger cheese. Good thing the army has plenty of gas masks lying around! His living quarters are flooded, leaving he and his bunkmates to sleep underwater using straws to breathe. And that's not the worst of it - there's still actual combat to look forward to. Although it's implied our hero is quite a good shot and capable of taking out more than a few of the enemy, at one point the fighting is so intense that he holds up a cigarette and lights it with a passing bullet. Explosions are frequent, and the air is filled with the sound of gunfire. Chaplin's message is clear, despite the slapstick antics: war is a terrible experience, no matter what news reel propaganda might have you believe.

The last half of the film follows him as he does the one thing you're not supposed to do when you're in the army - he volunteers for a secret mission. Of course, odds are it will be suicide, as it involves sneaking across enemy lines. He accomplishes this in typical Chaplin fashion, by doing something so absurd that nobody would ever suspect anyone to actually do it: he dresses up like a tree. This leads to some humorous chase scenes through a forest as German soldiers are unable to tell which trees are real and which aren't, allowing our protagonist time to knock them unconscious and sneak away.

Eventually, he finds a bombed-out home in which to sleep. Its owner turns out to be a French woman, played by Chaplin regular Edna Purviance. She mends his wounds and they do a little flirting, but are soon interrupted by a squad of German soldiers, which ultimately results in the woman being taken captive. Luckily, our doughboy is able to sneak in and knock out her captor before he "interrogates" (read: rapes) her. They're able to steal some German uniforms and team up with another captured soldier to escape. By disguising themselves as drivers, they're able to ride back to camp with the Kaiser himself (played by Chaplin's real life brother Sydney) in the back seat. They've won the war! Charlie's a hero!

Of course, as we all know, that's not how things really went down. It turns out that the vast majority of the film is a dream sequence. Our protagonist is still at basic training, and has yet to be shipped off to war. It's like Inglourious Basterds except more than 80 years earlier, and with an explicit acknowledgement that the fantastic ending could never have happened.

I'll be honest: while I found the comedy of Shoulder Arms to be hit-or-miss, the ending cements Chaplin as a brilliant satirist and socio-political commentator. While the film is much less subtle than a typical piece of war-time propaganda, it nonetheless spends most of its 46-minute runtime continuing to perpetuate the myth of war as a somewhat heroic and masculine endeavor (despite the harsh conditions). The main character is a bit of a moron, yet even he is able to outsmart dozens of German soldiers and even capture the Kaiser himself. If he can do it, then surely any American can! Because we're America, and winning is just what we do! By using the film's final shot to reveal that the whole thing is a dream, Chaplin immediately reverses all of the messages the film was supposedly promoting. It's as if he's screaming at the audience, "You know all that stuff you hear about war being heroic, and how America is the good guy, and we're going to win and overall this is a really great thing? Don't believe it! It's a complete and utter lie! A dream!"

I'll be honest: while I found the comedy of Shoulder Arms to be hit-or-miss, the ending cements Chaplin as a brilliant satirist and socio-political commentator. While the film is much less subtle than a typical piece of war-time propaganda, it nonetheless spends most of its 46-minute runtime continuing to perpetuate the myth of war as a somewhat heroic and masculine endeavor (despite the harsh conditions). The main character is a bit of a moron, yet even he is able to outsmart dozens of German soldiers and even capture the Kaiser himself. If he can do it, then surely any American can! Because we're America, and winning is just what we do! By using the film's final shot to reveal that the whole thing is a dream, Chaplin immediately reverses all of the messages the film was supposedly promoting. It's as if he's screaming at the audience, "You know all that stuff you hear about war being heroic, and how America is the good guy, and we're going to win and overall this is a really great thing? Don't believe it! It's a complete and utter lie! A dream!"

(Random side note: earlier in the film, as Chaplin stands miserably in the trenches, a split-screen shows images of the city as he thinks of home. This ultimate makes for a very intriguing device: a memory-within-a-dream. Or is it perhaps a dream-within-a-dream, nearly a century before Inception? Perhaps Chaplin means to imply that American society as a whole tends to be thought of rather idealistically, particularly in times of war? That our entire way of life is in many ways built on fantasy?)

That's the primary strength of Shoulder Arms. As a comedy, some gags work better than others. But as an anti-war film, it's extremely effective, and remarkably subversive. It's a movie about a brainless idiot that's actually very smart. In other words, business as usual for Charlie Chaplin.