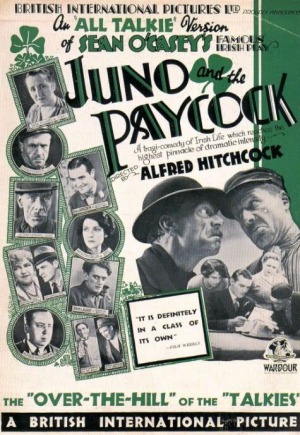

The Hitchcock Files: Juno and the Paycock (1930)

The Hitchcock Files is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at the filmography of Alfred Hitchcock. It should be noted that this series does not include his early silent films, though these are noteworthy in their own right.

The Hitchcock Files is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at the filmography of Alfred Hitchcock. It should be noted that this series does not include his early silent films, though these are noteworthy in their own right.

“All religions is passin' away. Take the real Dublin people, for instance. They know more about Charlie Chaplin and Tommy Mix than they do about S.S. Peter an' Paul.” –Juno and the Paycock

With the advent of sound and the unparalleled success of Blackmail, it’s no surprise that Hitchcock’s follow-up film was entirely a talkie. There would be no silent version. Sound was the biggest thing to hit cinema since the invention of the movie camera, and the studios were gung ho on using it as much as possible. Unfortunately, the technology at this point had still not been perfected, and the decision to use it in a film adaptation of the play Juno and the Paycock was probably not the best choice. The final product just goes to show that even with a master like Hitch at the helm, when the audio quality of dialogue is lacking (not to mention the heavy Irish accents), less is probably more.

Based on a play by Sean O’Casey, the film follows the Boyle family during Ireland’s civil war. The patriarch, Captain Boyle (Edward Chapman), is a lazy drunk who’d rather spend time squandering their meager finances in the pub with his friend Joxer than put in a hard day’s work. It’s up to his wife Juno (Sara Allgood) to make enough for them, their daughter Mary and their crippled son Johnny to survive. When Mary is courted by a wealthy benefactor who promises them a sizeable inheritance, the Captain quickly borrows money and spends it on extravagant living. Eventually it’s revealed that there will be no inheritance, Mary is pregnant out of wedlock, and Johnny has been killed by the IRA.

While O’Casey’s play was notable for its emphasis on Ireland’s working class, the film adaptation feels bland and spiritless. Chapman’s performance is over-the-top and exaggerated, suggesting he’d be better suited for a stage performance than a feature film. Sara Allgood provides a solid foundation for the film’s most dramatic moments, however, and many of the supporting actors outshine the leads. John Laurie is remarkably compelling in his performance of Johnny, capable of communicating more about the traumas of war with merely his eyes than many more seasoned actors could manage. Also of note is the fact that while Hitch himself does not make his trademark cameo in this picture, the opening scene contains the screen debut of Barry Fitzgerald as an orator giving a rousing speech about the need for unity.

Despite the relative strength of the actors, however, the cinematography is largely uninspired. Whereas in films like Blackmail Hitchcock showed his willingness to move the camera in interesting ways (the shot up the stairs to the villain’s room immediately springs to mind), here most shots are static and dull. It’s obvious that many scenes were shot sitcom-style with a three-wall set so the camera can never switch angle. Furthermore, Hitchcock himself stated in interviews that the new sound technology required so many people and such heavy equipment to work that production was often crowded and cramped – even if it was possible to move the camera, there probably wouldn’t be much room to move it. Whereas large portions of Blackmail were shot silently, Juno and the Paycock was filmed with the sound recorded entirely on set, orchestra included (it was impossible to edit sound at the time), and this clearly limited the options for creative camerawork. Hitchcock does what he can, with an occasional dolly or reverse track to liven things up, but the final result is still mediocre.

Despite the relative strength of the actors, however, the cinematography is largely uninspired. Whereas in films like Blackmail Hitchcock showed his willingness to move the camera in interesting ways (the shot up the stairs to the villain’s room immediately springs to mind), here most shots are static and dull. It’s obvious that many scenes were shot sitcom-style with a three-wall set so the camera can never switch angle. Furthermore, Hitchcock himself stated in interviews that the new sound technology required so many people and such heavy equipment to work that production was often crowded and cramped – even if it was possible to move the camera, there probably wouldn’t be much room to move it. Whereas large portions of Blackmail were shot silently, Juno and the Paycock was filmed with the sound recorded entirely on set, orchestra included (it was impossible to edit sound at the time), and this clearly limited the options for creative camerawork. Hitchcock does what he can, with an occasional dolly or reverse track to liven things up, but the final result is still mediocre.

The only mildly interesting thing about the film is the treatment of religion, specifically the theme of the problem of evil. Characters are frequently confronted with suffering, and whether or not God can exist in times of hardship. Juno manages to reconcile faith in a loving God with their troubled circumstances – “What can God do against the stupidity of men?” However, at the end of the film, Mary declares with sorrow, “There is no God!” Their problems have become too much to bear. Juno takes her grief to the Virgin Mary; in one of the film’s few intriguing scenes, Hitchcock cuts between her sobs and the Virgin Mary statue on the wall. The spiritual tone of the room is juxtaposed with sorrow, as if to ask, “How could God allow this to occur?”

The only mildly interesting thing about the film is the treatment of religion, specifically the theme of the problem of evil. Characters are frequently confronted with suffering, and whether or not God can exist in times of hardship. Juno manages to reconcile faith in a loving God with their troubled circumstances – “What can God do against the stupidity of men?” However, at the end of the film, Mary declares with sorrow, “There is no God!” Their problems have become too much to bear. Juno takes her grief to the Virgin Mary; in one of the film’s few intriguing scenes, Hitchcock cuts between her sobs and the Virgin Mary statue on the wall. The spiritual tone of the room is juxtaposed with sorrow, as if to ask, “How could God allow this to occur?”

Socio-political commentary aside, the film as it stands is one of Hitchcock’s minor works. Despite his love for O’Casey (he would later model the bum at the bar in The Birds after him), primitive technology and an unwillingness to stray from the play prevents his effort from feeling like a good (or at times even competent) film. It’s a problem that many film adaptations still struggle with: how to stay true to the spirit of the material while transferring it to a different medium.

Hitchcock himself seemed aware of this fundamental flaw. “The film got very good notices, but I was actually ashamed, because it had nothing to do with cinema,” he would later say. “The critics praised the picture, and I had the feeling I was dishonest, that I had stolen something.” Perhaps this explains why whenever he would adapt a literary work in the future (in Psycho and The Birds, for example), he would alter it to such an extent that it seemed completely separate from the source material. By staying away from the author’s vision, he was able to more fully realize his own, and use the unique gifts of cinema to communicate an entirely different experience.