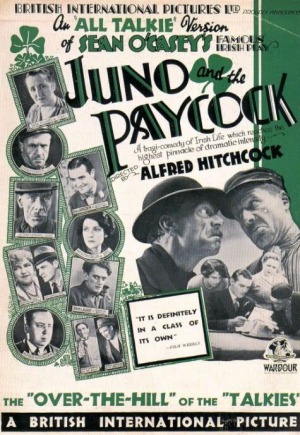

The Hitchcock Files is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at the filmography of Alfred Hitchcock. It should be noted that this series does not include his early silent films, though these are noteworthy in their own right.

The Hitchcock Files is a continual feature at The Kuleshov Effect. In these posts, I take a detailed and chronological look at the filmography of Alfred Hitchcock. It should be noted that this series does not include his early silent films, though these are noteworthy in their own right.

“All religions is passin' away. Take the real Dublin people, for instance. They know more about Charlie Chaplin and Tommy Mix than they do about S.S. Peter an' Paul.” –Juno and the Paycock

With the advent of sound and the unparalleled success of Blackmail, it’s no surprise that Hitchcock’s follow-up film was entirely a talkie. There would be no silent version. Sound was the biggest thing to hit cinema since the invention of the movie camera, and the studios were gung ho on using it as much as possible. Unfortunately, the technology at this point had still not been perfected, and the decision to use it in a film adaptation of the play Juno and the Paycock was probably not the best choice. The final product just goes to show that even with a master like Hitch at the helm, when the audio quality of dialogue is lacking (not to mention the heavy Irish accents), less is probably more.

Based on a play by Sean O’Casey, the film follows the Boyle family during Ireland’s civil war. The patriarch, Captain Boyle (Edward Chapman), is a lazy drunk who’d rather spend time squandering their meager finances in the pub with his friend Joxer than put in a hard day’s work. It’s up to his wife Juno (Sara Allgood) to make enough for them, their daughter Mary and their crippled son Johnny to survive. When Mary is courted by a wealthy benefactor who promises them a sizeable inheritance, the Captain quickly borrows money and spends it on extravagant living. Eventually it’s revealed that there will be no inheritance, Mary is pregnant out of wedlock, and Johnny has been killed by the IRA.

There was a bit of an upset at the 2009 Academy Awards when it came to the Foreign Language Film category. Though most critics predicted that the Israeli film Waltz With Bashir or the French drama The Class would walk away with the top prize, the award instead went to a small Japanese film many people hadn’t seen. As I haven’t see either, I can’t say whether or not Departures indeed deserved to win. However, I can say that it’s a good film, despite a formulaic plot and a score that frequently distracts from the film rather than enhancing it.

There was a bit of an upset at the 2009 Academy Awards when it came to the Foreign Language Film category. Though most critics predicted that the Israeli film Waltz With Bashir or the French drama The Class would walk away with the top prize, the award instead went to a small Japanese film many people hadn’t seen. As I haven’t see either, I can’t say whether or not Departures indeed deserved to win. However, I can say that it’s a good film, despite a formulaic plot and a score that frequently distracts from the film rather than enhancing it.

Departures follows Daigo (Masahiro Motoki), a cellist who moves back to his old hometown after his orchestra is dissolved. Desperate for a job, he spies a classified ad for “assisting departures” and decides to apply, thinking it’s most likely for some sort of travel agency. It’s actually a listing for a funeral home and involves the ceremonial cleaning and preparation of bodies in front of mourners before they can be placed in a coffin. Given the taboo nature of death in Japanese society, it isn’t exactly a dream job, but he decides to give it a try at the behest of the director, Mr. Sasaki (played to perfection by Tsutomu Yamazaki).

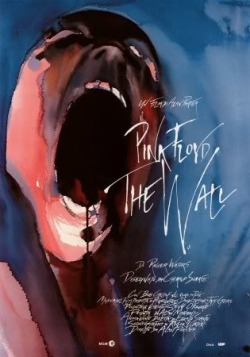

Are you:

Are you:

a) a fan of good music,

b) someone who doesn’t automatically dismiss any film described as “artsy,”

c) a consumer of hallucinogenic and psychedelic substances, or

d) a tortured soul consumed by angst and searching for your place in the universe?

If you answered “yes” to any of those, you’ll probably like The Wall, the 1982 musical film based around the Pink Floyd album of the same name. And if you answered “yes” to all four, it could potentially become one of your all-time favorite films - the cinematic equivalent of manna from heaven.

This post is not a review, but rather a more analytical piece in response to some of the debate surrounding Kick-Ass. It does contain spoilers. You have been warned.

This post is not a review, but rather a more analytical piece in response to some of the debate surrounding Kick-Ass. It does contain spoilers. You have been warned.

If you're even remotely interested in film or comics then you're probably well-aware that this weekend sees the release of Kick-Ass, the highly-anticipated (in geek circles) adaptation of Mark Millar's graphic novel of the same name. Marketed as a deconstruction of the superhero genre in the same vein as Watchmen, Kick-Ass follows superpower-less high schooler Dave Lezewski who decides to dress up and fight crime since... well, somebody has to do it. He teams up with a wealthy ex-cop named Big Daddy and his daughter Hit Girl and attempts to take on the city's bad guys, often with mixed results.

Kick-Ass has been causing quite a stir in critical circles. Roger Ebert found it morally reprehensible. Many have criticized its use of extreme violence involving minors. Others have argued it promotes the sexual abuse of children. Moral arguments aside, some have claimed that it fails as a satire, that it’s hypocritical in its deconstruction of a genre, and that it’s all style with no substance. While all of these concerns are certainly valid, and I can see the evidence for each of them, I can’t help but think they’re ultimately missing what the film is offering. After the first viewing, I might have agreed with some of them. But after seeing it a second time, I think there’s more going on beneath the surface of Kick-Ass than first meets the eye. In fact, I'm convinced Kick-Ass is downright progressive, due largely in part to three factors: its portrayal of women, its critique of mass media and the internet, and its honesty about why people consume films and comics.

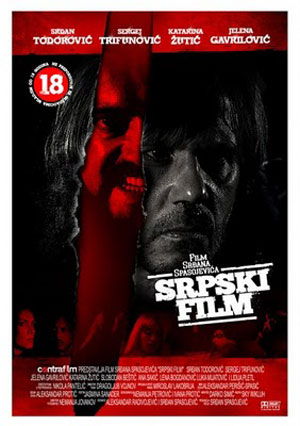

When the closing credits of Serbian Film began to roll, I could only sit paralyzed with my mouth drooping slightly and my eyes glazed over as I processed what I had just seen. My brain seemed unable to produce any sort of coherent thought, let alone come up with an answer to the question of what to do next. How should I respond? I spent the remainder of the evening not wanting to say much to anybody, preferring to sit in silence and attempt to figure out... something, I'm not sure what. I wanted to cry. I wanted to laugh. I wanted to scream. I wanted to have sex. I wanted to castrate myself. And I wanted all of these things equally. At some point during the climactic scene, I realized that I was a living example of the phrase "physically shaken," my arms and legs spasming like some sort of micro-seizure. It would not be an exaggeration to say I was reduced to a quivering mess of a man; Serbian Film chewed me up and spat me out, and that was that.

"I wanted this not to be a gay story or a straight story but to be a human story." --Tom Ford

"I wanted this not to be a gay story or a straight story but to be a human story." --Tom Ford

As anyone who knows me can tell you, I don’t really care much about fashion. It’s just not one of those things I find to be interesting or important. I hear the word “Prada” and the first thing I think of is Meryl Streep. But despite my complete and utter ignorance about this element of Western culture, I wasn’t surprised to learn that A Single Man director Tom Ford is the former creative director of Gucci and now runs his own fashion label. Who else would be able to combine framing, color and design into such memorable imagery?

Indeed, even if you walk away from Ford’s directorial debut feeling let down by the overall product, it can’t be denied that the man has a gift for the aesthetic. The film is set in the early 1960s and follows George Falconer (Colin Firth), a gay university professor struggling to cope with the death of his partner Jim (Matthew Goode). It’s been eight months since the fatal car crash, and George has decided that he can’t take the grief anymore. Today will be his last day before committing suicide. It’s a bleak premise, and the cinematography acts as a visual representation of George’s spirit.