Sunnyside was Chaplin's third film for First National Pictures. Although it received mixed reviews upon its released and was somewhat of a commercial disappointment, it still contains some solid gags, and is noteworthy for having what is arguably the most depressing ending in Chaplin's major filmography.

Sunnyside was Chaplin's third film for First National Pictures. Although it received mixed reviews upon its released and was somewhat of a commercial disappointment, it still contains some solid gags, and is noteworthy for having what is arguably the most depressing ending in Chaplin's major filmography.

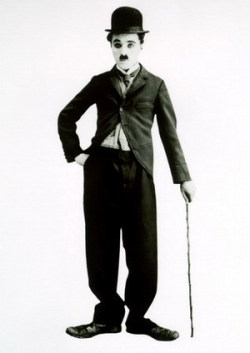

The plot finds Chaplin playing a farm handyman who also looks after the village hotel. He is introduced as such by a title card that is either one of the laziest title cards ever written, or a brilliant jab at the way many of them are composed: "Charlie the farmhand, etc. etc. etc." The opening scene finds him unwilling to get out of bed early in the morning, despite efforts by his boss to get him off to work. When he finally makes it downstairs to prepare breakfast, he gets it directly from the source. There are a variety of gags in this scene, most of which work, whether it's him waiting impatiently for a chicken to lay an egg or getting milk straight from the cow.

When he heads off to town, a fascinating title card pops up that establishes nature as Chaplin's religion of sorts: "His church, the sky -- his altar, the landscape." He's most fulfilled when working outside. This leads into another scene in which he loses a herd of cows, only to ultimately have to chase down a bull. The townspeople run after him, and he unfortunatedly falls off a small bridge and is knocked unconscious. This leads to a staple of Chaplin's early work: a dream sequence, which finds him frollicking carefree with a group of beautiful women through open fields. This is the happiest he'll ever be in the film (and arguably in any of his work), free to enjoy nature with people who might satisfy his loneliness. Unfortunately, like all things that are too good to be true, he must eventually wake up from the dream and rejoin reality.